This article has been adapted from Shri. Deepak Raja’s article ‘Pt. Omkarnath Thakur’, 18 Jun 2011, with inclusions from various sources listed below, for publication on the occasion of the Saptak Annual Festival 2017, which was dedicated to the memory of Panditjee. The publication also included a CD of clippings of Panditjee’s music from the archives, all of which have been made available below.

Playlist: Pt. Omkarnath Thakur from Saptak Archives

Introduction

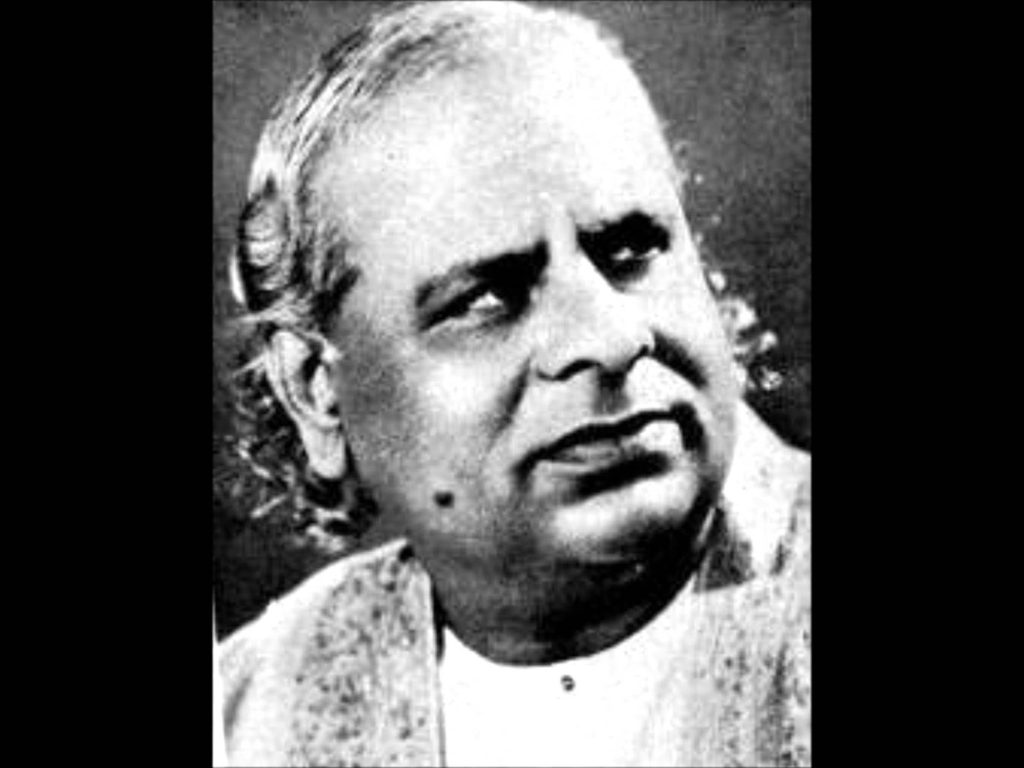

Pandit Omkarnath Thakur, regal in appearance and bearing, dressed in flowing silken robes, and sporting a leonine mane of shoulder-length white hair, accompanied by four tanpuras, two vocalists, and often two melodic accompaniments, is one of the enduring images of the last century in Hindustani music. On stage, Omkarnathji was living theatre, but he was much more than just a musician. He enjoyed a rare combination of stature and popularity as a teacher, administrator, theoretician, political activist, and an institution-builder.

Life

Pandit Omkarnath was born at Jahaaj in the Khambhat district of Gujarat on June 24th, 1897. His grandfather and father were both soldiers in the employ of the Peshwa rulers. Under the influence of a saint, Omkarnathji’s father, Gaurishankar, became a hermit and devoted his life to Pranava Sadhana — the exploration of the mysteries of “Om”, the primeval sound. This spiritual pursuit led him to name his last child Omkar.

Omkarnathji used to say that his father was gifted with many miraculous Yogic powers. He had foretold the exact day and hour of his death (in 1910). Prior to shaking off his mortal coils, Pandit Gauri Shankar called his favourite son Omkarnathji to his side blessed him with a betel-roll with which he wrote a precious “mantra” on the boy’s tongue !

Omkarnathji’s mother was cheated out of her husband’s share of the family’s assets, and left destitute, along with her four children. A strong-willed woman, she moved the family to neighbouring Bharuch, did menial tasks as a domestic servant, and brought up the children. From the age of five or six, Omkarnathji started contributing to the family’s resources by working as a domestic servant, as a cook’s assistant, as a labourer in a textile mill, and as an occasional singer-actor in local theatrical productions. When his father took to “Sanyas” and went to live alone in a little hut on the banks of the River Narmada, young Omkarnathji would run many miles and even swim across the Narmada so that he could reach his father’s hut, clean, sweep and cook for him and fill pitchers of water for his use! He fetched wood from tree branches floating in the river, which he would sell for money for his family.

When Omkarnathji was in his teens, he came in contact with Seth Shahpurji Doongaji, a philanthropist of Bharuch. The wealthy merchant noticed his talent and passion for music, and sponsored him for training under Pandit Vishnu Digambar Paluskar at the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya in Bombay.

For 6 years, Omkarnathji learnt the vocal art of the Gwalior gharana and the Pakhavaj, studied authoritative musicological texts, and served his Guru with devotion. Within this period, he acquired knowledge that the syllabus of the Vidyalay expected would take 9 years to learn. When his Guru decided to open a branch of his music school at Lahore, Omkarnathji – still in his early 20s — was sent there as its Principal. Working tirelessly as a teacher and administrator at the Lahore school, he also launched his career as a performing musician. After three years at Lahore, he returned to Bharuch to start a music school, and to launch himself in political activity. His music school was later shifted to Bombay in 1934, and thence to Surat in 1942.

His family circumstances had not permitted him to go to school in childhood. But, in his early years he had worked for a Jain religious establishment, where the monks taught him to read and write. Later on, by his own efforts, he mastered several languages – Hindi, English, Marathi, Sanskrit, Bengali, Punjabi, Urdu and Nepali. With himself as his only tutor, and his thorough study of ancient texts like the Natyashastra, Omkarnathji grew to be the most articulate orator and the most profound theoretician amongst musicians of the 20th century.

In 1918, his career took off with impressive concerts at the court of Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III of Baroda, and at the Harballabh Sangeet Sammelan at Jallandhar. A few years later, he visited Nepal at won the admiration of the King, who could not persuade Omkarnathji to accept his patronage. By 1930, Omkarnathji’s fame had spread far and wide, and he became a star attraction at every major music festival in India.

In 1931, he was invited to the International Music Conference at Florence in Italy. From there, he traveled to Germany, Holland, France, England, Wales, Switzerland and Italy (where he famously sang for Benito Mussolini), giving performances and lecture demonstrations. It was Omkarnathji who first ignited a degree of serious interest in Hindustani music amongst Western scholars and audiences three decades before they had heard the Elder Dagar Brothers, Pandit Ravi Shankar and Ustad Ali Akbar Khan.

Omkarnathji’s meeting with Mussolini deserves special mention and makes for an interesting story. Mussolini had heard of Omkarnathji’s theories and experiments regarding the inducement of emotional states by raga performances, and wanted a demonstration.

After a specially prepared vegetarian dinner, Thakur began with bhoop, which depicts valor. “When I was soaring in the high notes of the rāga,” he later recalled, “Mussolini suddenly said ‘Stop!’ I opened my eyes and found that he was sweating heavily. His face was pink and his eyes looked like burning coals. A few minutes later his visage gained normalcy and he said ‘A good experiment.’”

After Omkarnathji brought him to tears with rāga chhayanat, which is meant to depict pathos, Mussolini said, after taking some time to recover, “Very valuable and enlightening demonstration about the power of Indian music.”

Mussolini then returned the favor: Producing his violin, he treated Omkarnathji to works by Paganini and Mozart. Again, both agreed on the music’s power to evoke emotion.

“I could not sleep at all the entire night,” Omkarnathji recalled, “wondering whether the meeting had really taken place; I thought it was a part of a dream.” The next day, two letters from Mussolini arrived—one thanking him and one appointing him as director of a newly formed university department to study the effect of music on the mind (an appointment that he was unable to accept).

While earning laurels as a musician, Pandit Omkarnathji also involved himself actively in the freedom struggle. He was elected President of the Bharuch Congress Committee, and a member of the Gujarat Provincial Congress Committee. When India made its tryst with destiny at the stroke of midnight on August 14-15, 1947, Jawaharlal Nehru invited Pandit Omkarnathji Thakur to sing the national song, “Vande Mataram” at the Central Hall of Parliament House, from where it was broadcast nationally. In later years, his composition of Vande Mataram became, by public demand, almost a permanent feature of his public concerts.

When Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya was establishing the Benares Hindu University (BHU), he invited Pandit Omkarnathji to set up and manage the Department of Music. This could not happen during Malaviya’s lifetime; but it did happen in 1950, and Omkarnathji moved to Benares as the first Dean of the Music Faculty to serve there until retirement.. At BHU, he trained a group of outstanding musicians and scholars to build a centre of excellence. Amongst his most distinguished students were Dr. Premlata Sharma, whom he groomed as an eminent musicologist, Padmashree Dr. Balwantrai Bhatt and Dr. N Rajam, whom he nurtured into an outstanding violinist.

Another of Omkarnathji’s passions was the furtherence of research work in music. Always keen to experiment, he once tried, successfully, to calm an angry lion at a zoo in Lahore by requesting a friend to play the komal gandhar on his violin. The lion is said to have calmed down and become friendly. Omkarnathji was thus curious about the effect of music on the human mind and body and was keen that the government support research work in this direction.

During his tenure at BHU, he accelerated work on two major musicological treatises: Pranava Bharati, published in 1956, is landmark treatise on the theoretical aspects of music – swara, raga, and rasa and included his views on the ancient music Shastras. Sangeetanjali (in six volumes) published between 1938 and 1962, is a manual on the practical aspects of music performance, including raga grammar and aesthetics.

Between 1934 and 1961, Pandit Omkarnathji cut over twenty records with HMV in the 78 rpm, 45 rpm and Long Playing formats. Several of Pandit Omkarnathji’s radio broadcasts were posthumously published by All India Radio archives. The repertoire on his recordings consists of Khayals, bhajans, and patriotic songs. As a result, in the popular imagination, Omkarnathji is most widely recognized by his three Meera bhajans – Jogi mat jaa, Main Nahi Makhan Khayo and Pag ghunghroo bandh Meera naachi re – and his rendering of the national song, Vande Mataram.

In 1955, Pandit Omkarnathji became the first to receive the Padmashri award for Music. Among the other honours he received were the Sangeet Natak Akademi award, a doctorate from BHU and Rabinra Bharati University, The “Sangeet Prabhakar” award conferred upon him by by Pt. Madan Mohan Malaviya, “Sangeet Martand” from Calcutta Sanskrit Mahavidyalaya in 1940, and “Sangeet Mahamahodaya” from the ruler of Nepal in 1930.

All his life, Omkarnathji remained a stickler for his physical health. Apart from leading a thoroughly disciplined life, and always remaining very frugal in his eating habits, he devoted considerable time daily to physical exercises, swimming, and even the exercises he had learnt from the famed wrestler Gaama! Even in his late fifties, he is said to have continued most of these exercises.

While at BHU, Omkarnathji suffered a heart attack, recovered from it, and continued to perform. In 1965, he had a paralytic stroke which claimed his life on December 29th, 1967.

His legend, though lives on. The people of Surat still recall the time they approached him to relieve them of unforgiving famine. In 1948, when Surat was wrapped in famine with no signs of rain, and when everything else failed, the farmers of the region decided to approach Pt. Omkarnathji Thakur for help. Writer Bhagwati Kumar Sharma, 82, reminisces, “I was a 14-year-old teenager that year and a huge fan of Pandit Omkarnathji’s soulful voice. My neighbour, a Mahadevbhai Shastri, was Panditji’s pupil and I had been fortunate to see the sangeet samrat during his visits. In 1948, there was no rain in Surat during the monsoon. Thakurji lived in Surat then. The town’s people gathered and requested him to sing ragas of Malhar Yajya because they believed in the power of his voice. A stage was set up at Killa Maidan – outside the Surat Castle. Thousands gathered to listen to his rendition. Pandit Omkarnathji along with musicians and his constant companions playing ‘tanpuras’ mesmerized the audience. For three days, the town was soaked in the stalwart’s voice. On the evening of the third day, it started drizzling. Finally, Surat experienced monsoon.”

Musicianship

Omkarnathji had been trained only by Vishnu Digambar Paluskar, a thoroughbred maestro, and pioneering educator, of the Gwalior gharana. Rather than merely emulating his Guru’s musicianship though, Omkarnathji deviated substantially from the tradition, and became a daring innovator. In an era when khayal was still bound by the Dhrupad legacy of formal aloofness, Omkarnathji had the courage to adopt an emotionally charged, and even melodramatic, style of rendition. He freely introduced elements of Tappa and Thumree into khayal rendition, sometimes blurring the borders between the genres. In a milieu in which grammarians were taking over the organization of musical knowledge, he emphasized the esoteric aspects, and even experimented with the healing powers of raga-s.

To an extent, he was influenced by the doleful and sweet style of another Gwalior-trained maverick, Auliya Rehmat Khan (1860-1922); but his own deviations from Gwalior were more radical. Critical opinion therefore regards Omkarnathji as an original musician, though with firm moorings in Gwalior vocalism.

Omkarnathji is often considered a forerunner of the romanticist movement that surfaced in khayal vocalism in the 1970s with the emergence of Kumar Gandharva (1924-1992), Kishori Amonkar (Born: 1931), and Jasraj (Born: 1930). Omkarnathji was fond of Kumarji, who he called his godson. As an artistic ideology, romanticism signifies a preference for emotionally charged expression, along with relative indifference to the structural aspects of music. Omkarnathji exhibited a generous dose of classicism in his musical personality. But, with his emphasis on the explicit communication of emotional values through the khayal, he paved the way for later romanticists. Among the many musicians Omkarnathji’s music has inspired is the famed Carnatic Violinist Padmabhushan M.S. Gopalakrishnan whose style has been considerable influenced by Omkarnathji’s vocal style.

Like the later romanticists, Pandit Omkarnathji’s repertoire consisted primarily of Khayal and Bhajans. He never sang Tarana-s, Tappa-s or Thumree-s in public, although all these were part of the Gwalior repertoire in his times. His Khayal repertoire had a substantial representation of common ragas like Malkauns, Desi, Shuddha Kalyan, Chhayanat, Lalit, Todi and Komal Rishabh Asavari, and a moderate presence of uncommon raga-s like Champak, Neelambari, Devgiri Bilawal, Sughrai, and Shuddha Nat. He adapted a few Carnatic raga-s so comfortably, that they virtually lost all traces of their Carnatic origins. He selected them for their emotional content, and rendered them in his own unique style. His much loved rendition of Neelambari is exemplary of this.

There are clearly three facets to Omkarnathji’s personality as a musician. The first is his preoccupation with mystical aspect of musical pursuits, inherited from his renunciate father. The second is the scholarly facet, steeped in ancient musicological texts, whose wisdom he attempted to translate into performance. The third is the dramatic, even theatrical, facet which explicitly sought to create an impact amongst his audiences. How comfortably these facets cohabited in the same person is a matter of opinion. The combination, however, made him a colorful, and even, controversial musician.

With his conscious and deliberate use of “Abhinaya” in all its aspects – his dramatic Kaaku prayog (voice-modulations), Angaraga (tasteful elegant clothes), Mukhamudras (facial expressions) and Hastachalan (hand gestures) – Omkarnthji’s performances were spectacles of theatrical performance as much as they were serious expositions of music.

Pandit Omkarnathji had cultivated a monumental voice in terms of volume, range, and pliability. His faultless technique enabled him to cover two and a half octaves without any sacrifice of musical value. He made very effective use of volume and timbre modulations in order to heighten the emotional intensity of his renditions.

He had strong views on the emotional personality of each raga. In pursuance of these perceptions, he composed a large number of bandish-es in various raga-s under the pen-name “Pranav Rang”, published them in his six-volume work, Sangeetanjali, and performed them regularly at concerts. He tailored all aspects of his rendition of each raga based on his perception of it, drawn mostly from ancient and mediaeval musicological texts. This approach could sometimes lead to unorthodox architecture or apparently libertarian interpretations of raga-s as currently understood. But, most of the time, it was compelling music.

Omkarnathji had a rare ability to deploy the poetry of his khayals in a variety of ways and for achieving a variety of effects. While rendering the bandish, he treated the poetic element with great respect as literature. In rhythmic play, however, he could mutilate the words, treating them, effectively, as clusters of meaningless consonants. And, as evocative expressions, he could use them virtually in conversational deployment. The various ways in which he enunciated selected phrases, along with melodic variants, almost approached the lyrical sophistication of the Thumree genre.

Not surprisingly for his stature, Omkarnathji’s khayal architecture was impeccable, except in a few raga-s, like Nilambari, in which the emotional content of the raga was suited only for slow-tempo compositions and improvisations. His virtuosity was formidable. His tan-s were epitomes of effortless agility and complexity, comparable to the best in his era. Occasionally, there was an element of exhibitionism in them. But, even conservative audiences accepted this as a part of the total package that was Omkarnath Thakur.

Quotes

Mahatma Gandhi: “Pandit Omkarnath can achieve through a single song of his, what I cannot achieve through several speeches.”

Prithviraj Kapoor: “Omkarnath Thakur’s dramatic presentation of songs should not only be heard, but seen too!”

Dr. N. Rajam: “The most striking feature of my guru’s music was the evoking of emotions in the minds of listeners through the media of swara, sahitya, appropriate facial expressions, Kaakus (voice modulations) etc. His tender and deep emotion found an ideal vehicle in his soft and sonorous voice. The pains and privations that he suffered in life resulted in a unique emotion-packed music.”

Smt. Sushila Mishra: “I still remember how at a huge music conference in Calcutta many years ago, the audience requested Omkarnathji to sing Neelambari. But he begged to be excused as Neelambari had been a favourite of his late wife Indira Devi and he felt he would have a breakdown if he tried to render it that evening! He always cherished memories of his wife’s devotion gratefully.”

Dr. N. Rajam: “It was a pity that he had to lead a lonely life all through. He had neither a house of his own, nor a relative to fall back upon in his old age, nor even a reliable servant to look after him. It was a pathetic sight to see him at the ripe age of 65 sweep the floors and cook his food all by himself. He used to remark that it was not in his luck to have a settled home. At the fag end of his career, when he did buy a house at Broach, the cruel hand of Fate prevented him from settling down there.”

References

- Raja, Deepak. “Pandit Omkarnath Thakur (1897-1967).” Deepak Raja’s World of Hindustani Music:. N.p., 18 June 2011. Web. 03 Oct. 2016.

- Misra, Susheela. Great Masters of Hindustani Music. New Delhi: Hem, 1981. Print.

- “Omkarnath Thakur.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 03 Oct. 2016.

- Nadkarni, Mohan. “Pt. Omkarnath Thakur.” The Lost World of Hindustani Music. N.p.: Rupa, 2004. N. pag. Print.

- Ranade, Ashok D. Some Hindustani Musicians: They Lit the Way! New Delhi: Promilla &, in Association with Bibliophile South Asia, 2011. Print.

- “Thakur and Mussolini.” Bibliolore. N.p., 24 May 2013. Web. 03 Oct. 2016.

- Khurana, Ashleshaa. “When Pt Omkarnath’s Malhar Rendition Pleased Raingods.” The Times of India. N.p., 18 July 2015. Web.

- “Omkarnath Thakur 78rpms” Rajeev Patke Homepage. N.p., 19 Dec 2006. Web. 03 Oct. 2016.

- Garg, M. (Ed.). (1997, June/July). “Jab Pt. Omkarnath Thakur Sangeet Karyalay Mein Padhare”. Sangeet.

A great effort, indeed, to share this with us all!

A very exhaustive narration of a Giant in Indian Music. This describes the Man who will always be unique, one of a kind genius that India gave birth to. I was fortunate to attend his last

performance in Sion,Mumbai in 1962/63 where he mesmerized the audience with: Vande Mataram and Jogi Mat Ja. His magical voice ‘BULAND Ahwaz’ cannot be matched by anyone. Pandit Shree Jasraj came very close! When he sang Vande Mataram the

audience stood up in awe!

Thank you for the kind words!

Thank you for such gem of songs, never getting enough of them. a great stress buster